The truth: I’ve been sitting on a draft of these thoughts for over 3 months now. It became a behemoth of a post, with nearly 2,000 words and counting, that I still didn’t feel captured my takeaways properly. So, instead of hemming & hawing (and only ever posting about music—oops), I’ve decided to release the original post in 3-ish parts.

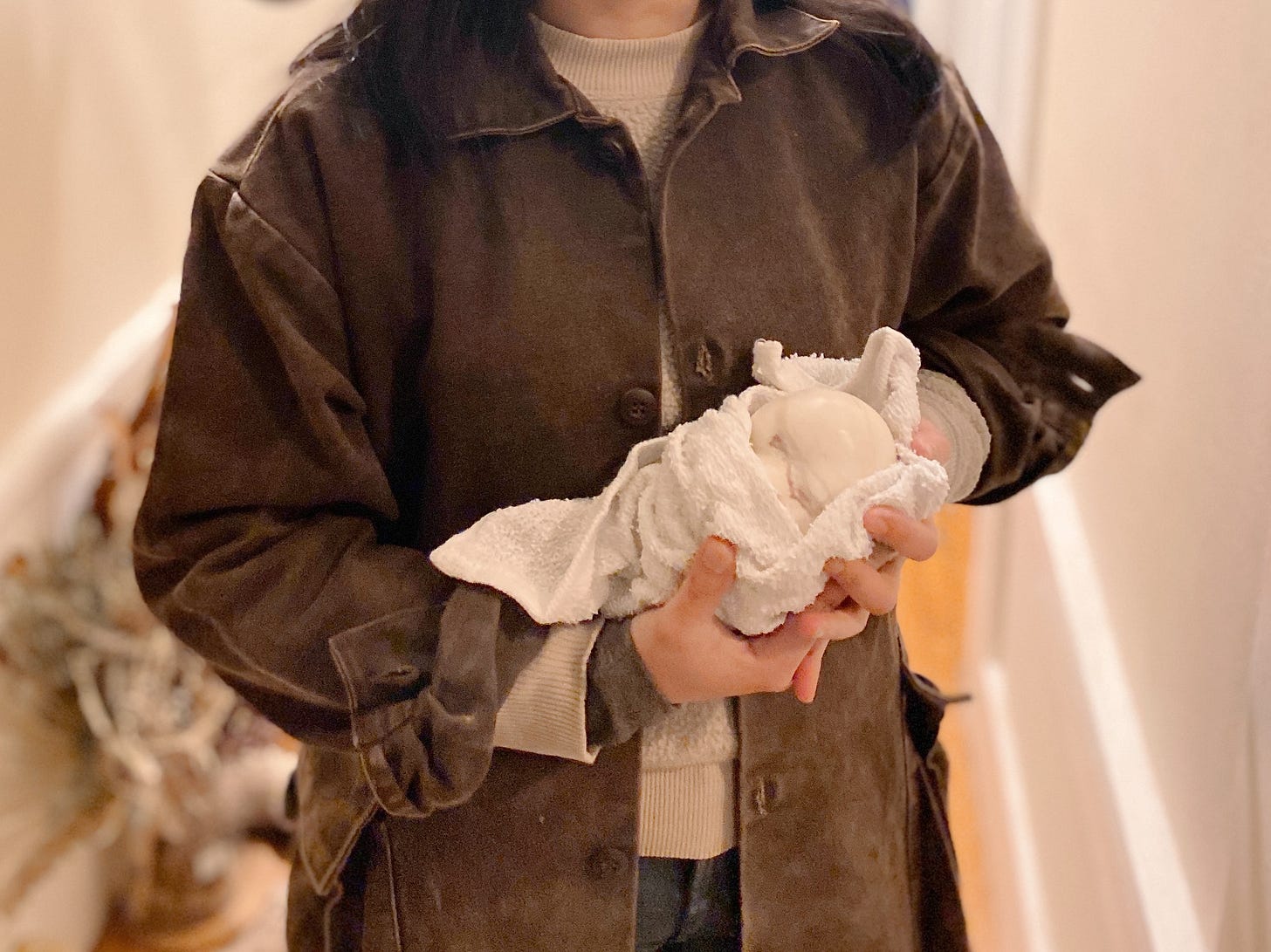

This past June marked the completion of my stone carving class, and the “marathon, not a sprint” adage was never truer. For nearly three months, I devoted my Thursday evenings to chiseling away at a 10-12 lb. chunk of alabaster (a soft stone, I’m told)—a frustratingly meditative practice and a bittersweet antidote for a lot of heavier questions I’d been asking myself about my own art making. At the same time, I took a needed break from carving wood—a decision I made independently of this class—but it did give me some space, energy, and kindness to my body that I really needed to see those 10 weeks through.

In keeping with the tone of the first session, there were never any lectures. No theory. No project prompt we were all aiming to fulfill. It was simply learning by doing, and all of the most illuminating takeaways came from asking my own questions or eavesdropping on other students’ conversations with the instructor. His style was infuriatingly simple—the type where you didn’t know you were being taught deep life lessons unless you figured them out for yourself. He wasn’t withholding out of spite; it was like he was blissfully unaware that everything he said was dripping with significance.

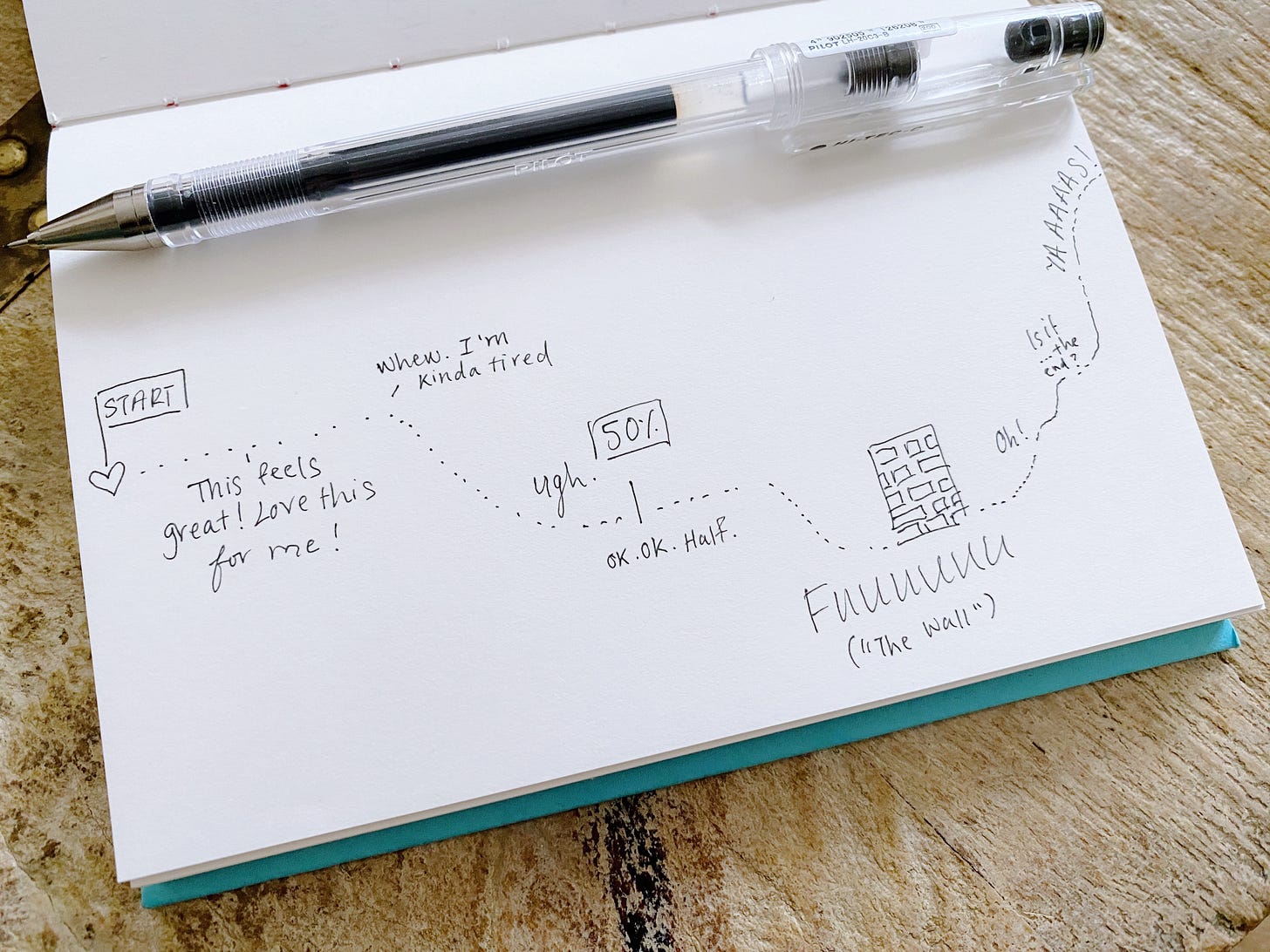

This was my first diamond in the rough, unearthing the arc of my struggle with hard things (literally, figuratively).

All in Favor of Burning Your Ships

I can’t even begin to tell you how many of these sessions I didn’t want to go to, with my workweek exhaustion hitting hard by Thursday night. My partner, A, was my life raft in the late evenings who would come by car to get me. But sometimes I wanted to text that life raft and urge him to arrive earlier so I could flee my own frustrations. I fired off a few of those texts. He never arrived before the class’s end time.

I’m picturing a roller coaster—not the kiddie type but the one that makes you sweat a little and they have to shut it down when the wind conditions are even a little unfavorable. I might feel apprehension and a feeling of not wanting to get on it when I’m waiting in line, and dread as I get into the car and the safety bars are lowered into place. But once I’m in and the teenager they staffed to operate the ride gives the wave, I have no choice but to go all the way to the end. There’s simply no way out.

The catch: most hard things in life don’t just last 12.4 seconds where you scream your heart out and call it a day, I guess. Maybe it’s more of a roller coaster in slo-mo where you feel every rise, fall, loop, and corkscrew deeply. And the slower it moves, the stronger the urge to want out.

The Wave of Working Through It

A momentary tangent: When I’m running, no matter how long I set out for, I always find myself spinning through the same cycle: I feel good—strong, even—in the first 25%. After I hit that mark, things go downhill and the slog is real from 25-75% with a slight reprieve at the halfway mark, depending on the day; some days I think, “Great. Now’s the turning point.” and other days I feel like going for another “half” will be the death of me. I remember looking at an illustrated map of a race I ran. Right at the 75% mark, there was a cartoonish brick facade with block letters labeled THE WALL. But, without fail, once I break through and it clicks that the end is near, I find a small reserve of energy and somehow manage to push through to the finish.

Each class followed this cycle to a T. If I look at the timestamps when I would text A to rescue me, they’d always fall in that 25-75% block when the work was arguably at its shittiest and I was starting to feel pain and frustration without any sense of progress. I always wanted to put down the tools and head home.

With stone carving, progress was frighteningly slow with only a hammer and chisels at our disposal. Working for an entire session barely shifted the shape of the stone I started with or, even worse, it started to look like a pile of shit. Truly. It took the shape of an emoji turd for weeks.

I think this is why it’s so easy to lose hope and momentum in the creative process. But the truth is: every time I make something, I will always always always reach the Turd Phase, or The Wall. In fact, it’s entirely possible that a majority of the process is the Turd Phase. Artists get a lot of credit for having the imagination (“The Eye”) to come up with their ideas, but as I start to see my vision take a not-so-lovely shape in reality, I can’t help but feel absolutely crushed by the disparity. I wonder if what distinguishes an experienced artist from a newer one is the ability to keep that vision alive through the roughest parts—the parts that external viewers never see.

Trust the Process (Not the Results)

…Hm, how do I explain this clichéd statement without making it sound cliché?

According to a quick punch into Google, the definition of “trust” is a “firm belief in the reliability, truth, ability, or strength of someone or something,” which is a pretty emotionally neutral definition. I think we as humans want so badly to imbue it with positivity. If I trust someone with my life, I imagine that this golden person would never harm me or may even have the ability to save me.

But if we focus on reliability and consistency as the source of trust, we can also trust things that don’t necessarily play out so heroically. Maybe this is what I mean by trusting the process.

I feel a little miffed when people say, “Things will work out in the end” in life, in art, etc. It puts the entire pot of gold at the very end of the rainbow, so my impatient ass is trying to rush to the end of the tunnel only to find… mixed results.

If I need reliability in order to trust, well… I can’t really trust in results, then. But after I noticed my mental process while running, I started seeing how often it played out in other areas of my life, especially as I carved the same stubborn block over many weeks. The arc was nothing but reliable: an excited beginning; a frustrated middle; a re-energized push to the finish.

Most of the time, I don’t know if I’ll feel pleased with a piece until I’m 99% done (and even then, the doubt can continue indefinitely), but I’m learning to trust that if I let myself ride this wave without jumping off, I will have made or done something. The result may be diamonds. It may very well be trash. It’s likely somewhere in the middle. But it’s not nothing.

As I take these observations with me into my own practice, I find that maybe I have to create some artificial sense of burning my ships, whatever that may be, because there’s something about the artistic process that necessitates that I break through THE WALL.

The dilemma: Left to my own devices, flight is almost always more readily available than fight. When I’m carving away alone in my makeshift space, I hit The Wall all too often. Several times in one project, even. A combo of my lack of willpower some days and the ease with which I can just pack it up and do something else gives me too easy of a liferaft instead of going head-first into the wave. Sure, I know there’s value in returning to something with fresh eyes, but I also want to train myself to confront the feeling of quitting too soon and losing out on the chance to create in spite of frustration.